These old-fashioned skills can help you get your boat on and off the dock smoothly

PAT MUNDUS FEB 27, 2019

My mother of all docking humiliations happened more than four decades ago. Docking a catboat with no engine and with no choice but to make a downwind approach, I thought we had a sufficient plan: sail into the marina basin, round up, drop the mainsail and slowly drift downwind onto the face dock.

We scandalized the gaff-rigged sail, lowering the peak halyard to reduce the sail to about half its normal size. Then we made a few passes back and forth across the opening in the bulkhead to assess the power of the wind and the way of the boat. We squared away for our approach, confident that our practice and planning would pay off.

That big old main boom was long, with just enough width for us to sail through the break in the bulkhead. Everything went well until the clew outhaul line on the outer tip of the boom made an uninvited acquaintance with a long nail on a piling. The poor boat came to a screeching stop and began to weathercock around under the boom. All hell broke loose, and we were appalled to find ourselves fending off in a maze of docked boats, struggling to get the sail down at the same time.

Lesson learned? We should have used the natural forces to help, not challenge us, and with no choice but a downwind approach, we could have paddled in—a controlled method. It was a humbling, teachable moment, all right.

Very few of us attempt docking under sail these days, but the way we handle our boat (power or sail) while coming alongside or getting off the dock is still one of the most satisfying seamanship abilities. It’s also one of the most important skills because proper technique prevents damage to our own boat and to others. Using dock lines to best advantage in conjunction with the engine certainly beats manhandling the weight of the boat. And last but not least, performing no-fuss line handling ensures smooth interaction among shipmates.

“But I have a bow thruster,” you say. Perhaps one day it might not work when you need it. Twin screws? Same sentiment. Although the following information is primarily for single-screw vessels, which need the assistance of dock lines, it never hurts for everyone to understand old-fashioned seamanship skills.

Basics first. If your deckhands don’t already know how to coil and reliably heave a line to the dock, then have them practice until they do. Most docklines are three-strand nylon or braided core with eye splices. Eyes are best sent ashore, where they can be dropped easily over pilings. In the event that you share a piling with another eye, you can get it off without disturbing the other by “dipping the eye.” That is, run your own eye up over the piling and drop it through the other eye. In this way, both eyes can be removed without disturbing the other.

Make sure your deckhands know commands such as “surge” (slack a line suddenly, but in a controlled manner), “take up” (pull slack out of line), and “hold” (keep the line as is without making it fast), so docking can be accomplished with as few words as possible. The need to keep lines clear of the propeller is imperative.

Also make sure your crew understands the safety hazards of loading (the strain on a line), pinch points (places where a body part might get caught) and the recoil area (the place where a line could spring back if it parts). You can control your vessel’s docklines, throttle, rudder and fenders. What you cannot control are wind, current and crowded marinas with inexpert shore crews—all the more reason to know how to use your docklines to best advantage.

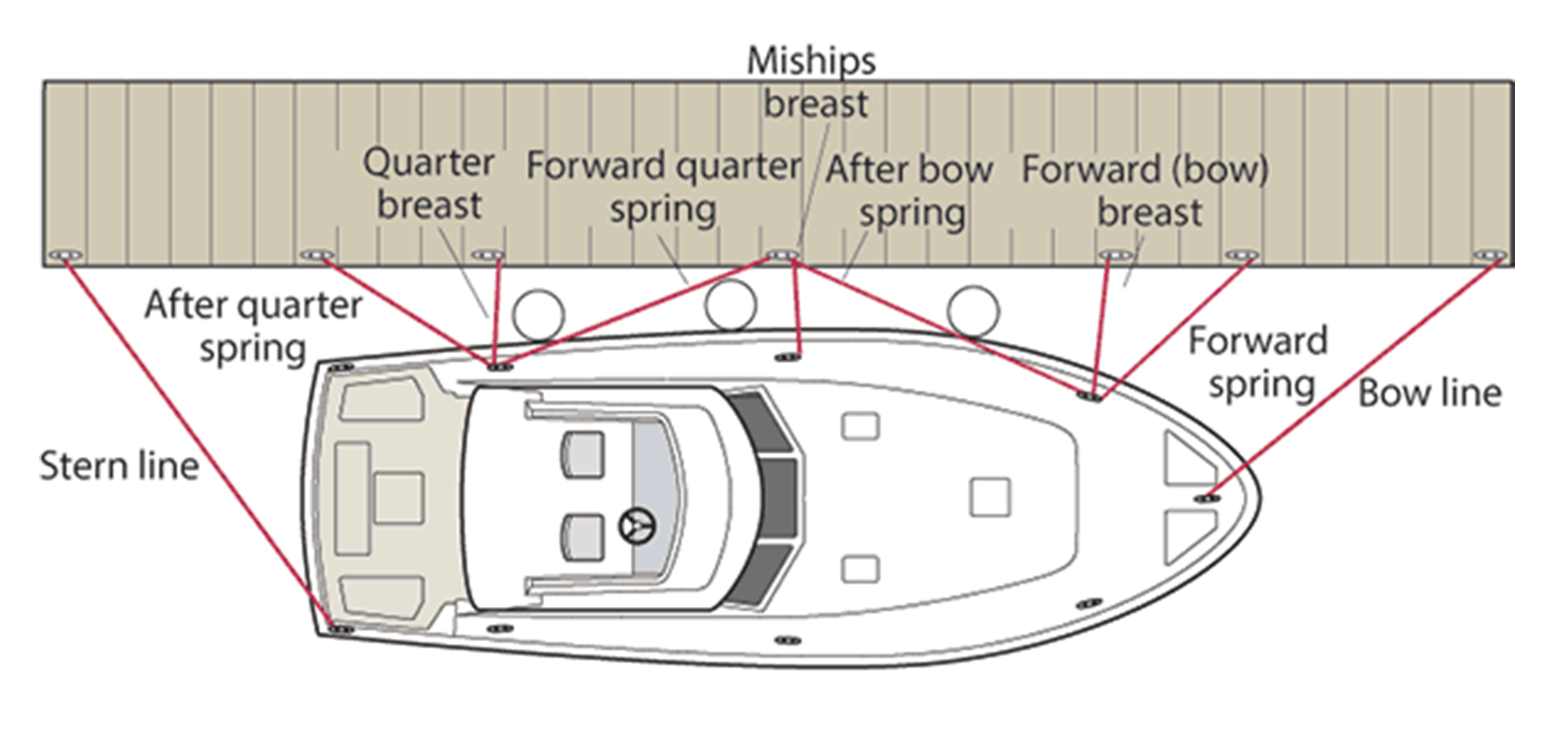

Docklines and their usage are properly named according to where they are made fast on the boat, and which direction they run ashore. Most of us speak casually about bow lines, stern lines and spring lines. Technically, a bow or stern line can lead ahead (forward spring), aft (aft spring) or athwartships at a right angle (breast line). If you are lucky, your boat will have amidships chocks and cleats or bitts. In this case, the amidships spring lines are named according to which direction they lead on the shore: forward or abaft the chock.

Depending on the configuration of the dock layout, the ideal minimum for most boats is a bow and stern line, and a forward and after spring line.

A breast line is most commonly used temporarily to hold the boat close to the dock in an offshore wind, or to keep the boat snug to the dock for boarding. A line “on a bight” is one rigged fast to the boat, run around a dock piling or cleat, then brought back to the boat. It’s useful when there is no one on the dock to release your lines. Slip one end, pull it back to the boat, and you’re clear.

Weight, depth, windage, pivot point, type of propulsion and horsepower, prop walk—all contribute to each vessel’s handling characteristics. Get to know the particulars of your vessel. Do you have an inboard engine with a right-hand propeller? Most single-screw recreational boats do, meaning the stern will tend initially to starboard in forward gear and to port in reverse gear.

Also, get to know the abilities of your crew. Once you understand how these factors all work on your boat, they become predictable traits. Practice.

When getting on or off the dock, plan your maneuvers in advance. Consider the direction of the wind and current, and use these factors to your advantage. Make a strategy and have a brief meeting with your crew so everyone knows what the goal is. Set the lines in place in advance. If you have shore line-handlers, get them on the same page, too.

When you are at the helm, issue clear orders to each person to create a coordinated, controlled effect, rather than allowing individuals—both on board and on the dock—to act independently. Be aware that some events require swift, bold and adaptive maneuvers. This is where practice and calm judgment will pay off most. If your planned docking attempt proves untenable, then back off and regroup for a second approach. Ignore onlookers (or, worse yet, unsolicited advice) and have confidence in your decisions and instincts.

If you have the choice, dock with the wind and current on the bow. Keeping the boat head-to-wind and to the current allows maximum control because you can use the throttle to maintain position or to advance. You can angle the bow across the wind and current, letting the wind and current set you to port or starboard without gaining headway. A purposeful bump of the throttle against the rudder will bring the bow back into the wind and stop the vessel’s set. The same goes for getting off the dock: Positioning the bow so the current and wind get between the dock and your vessel will encourage the natural forces to wedge you off the dock.

When the wind is on the outboard beam in a side-tie docking scenario, slowly approach the slip, take your way off and allow the natural forces to set you into the dock. This is where well-placed fenders come into play, allowing the boat to place herself alongside.

Getting off the dock with natural forces on your outboard beam is more of a challenge, but powering ahead against an aft-leading spring line from the bow with the helm toward the dock will kick the stern away from the dock, making room to back away. Remember to have a forward fender at the ready and/or have someone on the dock to fend the bow off. If you’d prefer to kick the bow out, power astern against a forward-leading spring line from the stern, adjusting the rudder as needed. Again, have fenders in place and be prepared to fend off the stern.

When approaching a bow-in slip with natural forces on either beam, gauge the set of the forces, allow room for the wind and current to set you into position, and have your crew ready to place the windward dock lines first.

Often, the only solution to getting alongside with the natural forces on your inboard beam is powering against an aft-leading spring line with the helm away from the dock. Also use this technique when you must maneuver into a side-tie slip with other boats made fast both ahead and astern of your slip.

In both cases, place the bow in close enough to throw a spring line to the dock attendant and have it made fast well aft in the slip with no slack. This will prevent your boat from traveling ahead. Gradually applying forward rpms with the helm hard over, away from the dock, will kick the stern in and gradually move your vessel to the face of the dock. We all have our own docking triumphs and failures. My hat’s off to seasoned boaters who dock without fanfare and keep their wits about them when circumstances are difficult.

Successful docking in challenging conditions is one of the biggest rewards of pleasure boating. Using a spring line to maneuver my own single-screw cruising boat gracefully into a slip between others with only a few feet to spare is enormously satisfying. “Nice job, skipper,” is a compliment I never take for granted. It comes with practice.

Successful docking in challenging conditions is one of the biggest rewards of pleasure boating. Using a spring line to maneuver my own single-screw cruising boat gracefully into a slip between others with only a few feet to spare is enormously satisfying. “Nice job, skipper,” is a compliment I never take for granted. It comes with practice.

This article originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of Soundings